Aerated concrete and EHCPs

I was up until midnight last night trying to battle a local authority Education, Health and Care Plan system (EHCP). The system itself is essentially unusable, so the council maintains a parallel system of Word documents and secure mail. Educational psychologists, schools and parents end up maintaining their own ad hoc systems too. I had to download a copy of Microsoft Word to try and the track changes — the ones that were just crossed out and the ones that were meant to be actual changes. ... moreGiven question of government use of X has come up again, I’d like to make the argument for the creation of micro.blog.gov.uk that uses the indieweb.org/Micropub standard + syndication as white label product that can be used by HMG, devolved government, local etc.

MPs on the select committee said the UK needed to develop greater “sovereign” technology capacity, award more contracts to smaller, local providers, and be less reliant on deals that resulted in government departments becoming locked into services with US firms.

I saw a band called TheWheel2! at the Windmill in Brixton at the weekend. At the time I wrote down ‘Dylan goes electric then goes new romantic’, which I’m not sure stands up on a second listen, but they were very good:

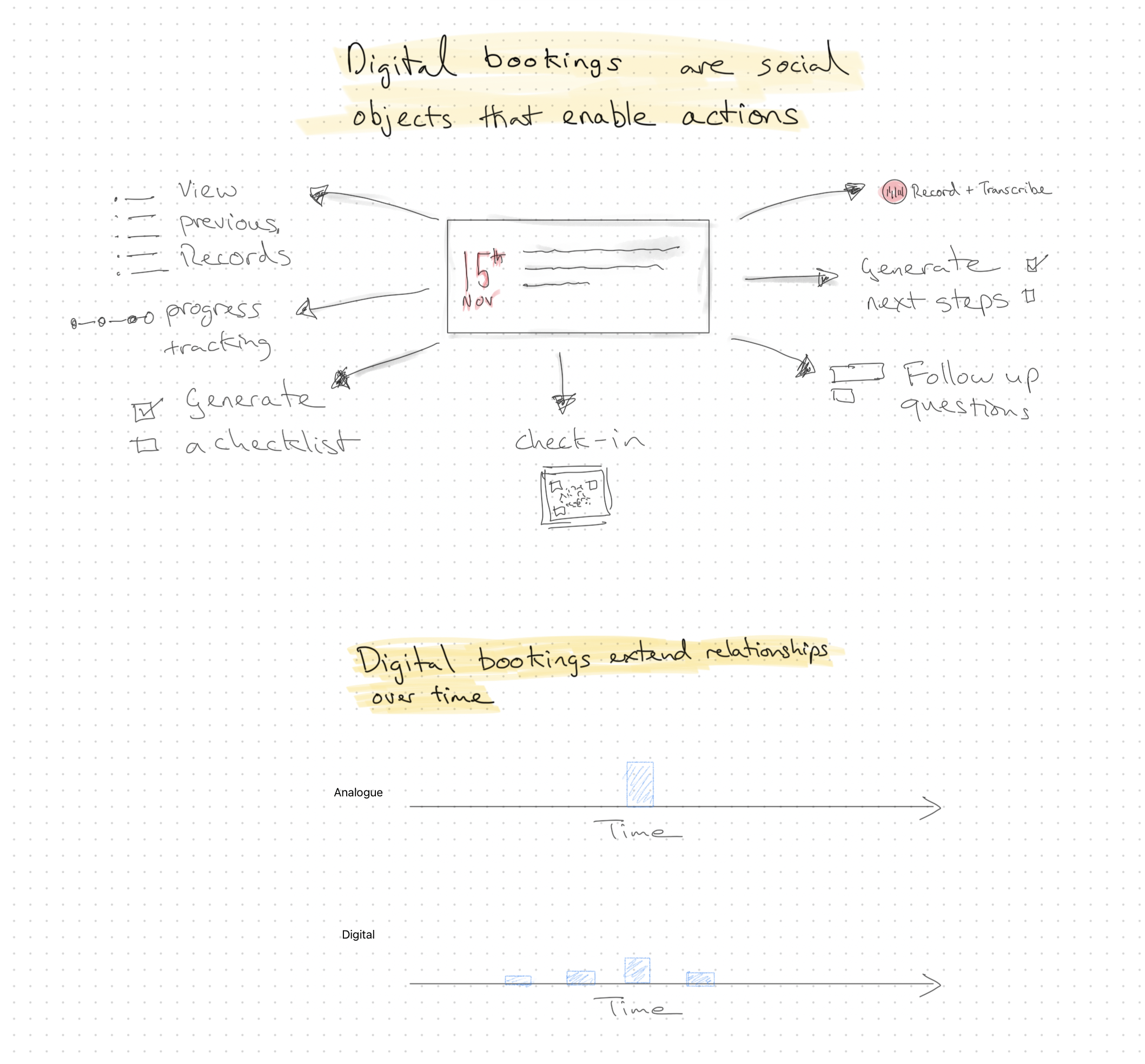

Some design provocations about preventative healthcare and designing for the service loop …

Preventative healthcare: designing for the service loop

Also on Medium: medium.com/@richardj…

Includes: why designing for preventative healthcare is a bit like BERG’s Here & There horizonless projection map of New York

Some (slightly belated) thoughts on the UK announcability-first announcement on digital identity: Digital identity and the UK government’s announceability problem

If it was easy to improve patient experience of NHS admin it would have been sorted long ago. The depth and breadth of admin failures that many people continue to experience suggest that fixing admin is a highly complex area that requires resources, skill, leadership – and, perhaps most importantly, standing in the shoes of patients and carers and seeing admin from their perspective.

First visit in years to the common land where I grew up. Hard to describe quite how much it is a part of me. The colour of the sand, the details of the small handful of types of plants that grow there are beyond familiar. Recognising individual trees from 40 years ago everywhere. Cheesy but true.

I enjoyed this interview with Michael Heseltine:

Hard to disagree with this diagnosis:

This repeated failure to deliver people’s aspirations after the 2008 crash, Brexit and Covid means we now have this political momentum for change and, with it, populism. It’s a race to the bottom and, sadly, Farage is winning.

I really hope someone makes a road trip film about this:

we [Thatcher and Heseltine] were never friends. Ken Clarke was a friend and so was Douglas Hurd. “We all went on holiday to the Galapagos and saw the blue-footed booby, an exotic bird.”

I keep wondering when the input methods for LLMs will start to diverge from familiar chat and voice interfaces. A few links to things that seem relevant:

This talk from 12 years ago shows a coder who created a domain specific language for coding python by voice:

[www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SkdfdXWYaI

This paper discusses “Pen-Centric Shorthand Handwriting Recognition Interfaces”:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/4488861

SkipWriter was a recent attempt at LLM-Powered Abbreviated Writing on Tablets:

https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3654777.3676423

The authors say:

Abbreviating with LLMs presents novel and largely untapped potentials for text input.

Shorthand-Aided Rapid Keyboarding (SHARK) was a keyboard replacement for iPhone and Android:

A future where public servants spend their time on hold to Palientir to get anything done …

he complained in an email to Palantir. Four months later, his case was still visible to other officers, and he was still sending emails to Palantir to fix the problem

How Palantir, Peter Thiel’s Secretive Data Company, Pushed Its Way Into Policing | WIRED

I’ve heard the term “digital by default” pop up a few times recently, so I dug out the original definition from the UK Government Digital Strategy:

Digital by default means digital services which are so straightforward and convenient that all those who can use digital services will choose to do so, while those who can’t are not excluded.

I had an opticians appointment the other day and have some standard age + UV based degradation. The preventative healthcare answer to which is 1) kale 2) hats. So, London based hat wearers, any suggestion of hat shops for men of a certain age?

Booking marking this case study of GOV.UK Notify from Hannah White and @eaves.ca to wheel out next time there’s a bit of reductive technical solutionism about common platforms. Scale by starting small and thinking about adoption. Scaling Digital Infrastructure in a Siloed State

Because software is eating the world, there are now theology articles in Wired. (I started reading and couldn’t stop).